In my lifetime being connected to an always on computer network, the internet, has changed almost everything: from what you for a living; how to file your tax return about that employment and how your order form your local takeaway when you get home. Some things seem to have radically changed very quickly. When I first started working on digital advertising with major UK publishers, editors held-back news stories for the printed edition (next month) rather than post in today’s online news. I guess, they’re now tweeting it for themselves first as there’s no printed edition of many of those publications any more.

But, will the Internet kill television in the UK?

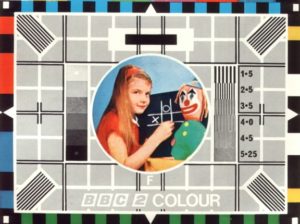

Television has behaved a little differently. When I was born there were only 3 UK television channels and not everything was broadcast in colour. Fast forward to when I was 12 and the Whiteley-Vorderman duo hosted, effectively, the first programme (Countdown) on the fourth channel. It was a slow and highly regulated evolution.

As with everything, over then next 30 years the pace of change increased. The UK went through the dish wars with the Sky-BSB years (check-out these BSB promos promising five channel television: they feel very dated indeed now) and a fractured cable industry only really came to be a player with the merger of NTL and Telewest in early 2006.

I guess it was February 2005 when video on the truly internet arrived (YouTube launched) but I think you can be forgiven for looking at the media landscape back then and thinking the internet was primarily for the written word even if, within 2 years, Netflix was launching a DVD streaming service. But the internet develops video models for business very quickly. Just this week, YouTube announced it will stop supporting the 30-second unskippable advertising format that has been the backbone of broadcast TV for decades. Can television continue to hold on to that model?

A couple of weeks ago, The Economist ran an article that explains some of the economics of television and how they are changing.

The internet has already changed what viewers watch, what kind of video programming is produced for them and how they watch it, and it is beginning to disrupt the television schedules of hundreds of channels, too. But all this is happening in slow motion, because over the past few decades television has developed one of the most lucrative business models in entertainment history, and both distributors and networks have a deeply vested interest in retaining it.

Television’s $185bn advertising business is a hefty war-chest to fight the challenge of change. I wonder how it will look in five more years? Will it be radically different – in the way printed media is now so different – or, like its broadcast parents, will television for the internet continue a slower evolution?

I also wonder when my own habits will change. When will I consume more content delivered via the broadband connection than over the broadcast air? It can’t be that far away.